The Timeless Allure of the Strong Man

Benito Mussolini, Fascist Italy, and the Power of Humility

Lately, I’ve been studying Italian history. A portion of my novel-in-progress takes place in Naples, in the years just before and during World War II, and it turns out, if you hope to write a novel, it helps if you know a little more than a high school junior taking AP History.

When I got started, I knew exactly five things about Italy in WWII. (1) Benito Mussolini gave a lot of speeches. (2) At some point, Mussolini declared himself dictator. (3) When the war broke out, he decided his country would fight alongside Hitler and the Nazis. (4) But Italy eventually switched sides and helped the Allied Powers. (5) Mussolini was ousted from power, tried to flee, and was ultimately assassinated.

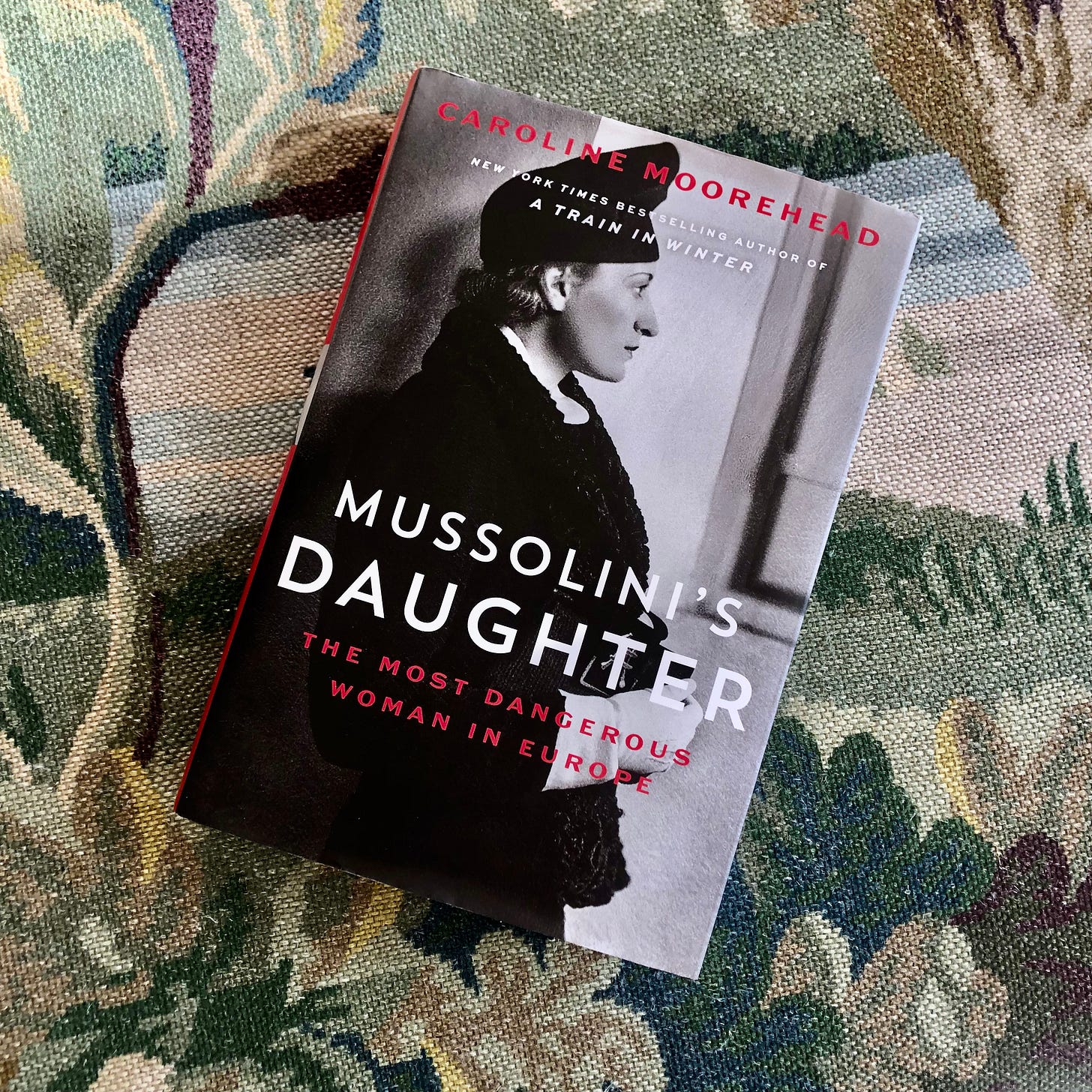

I needed more. So I got to work, reading everything I could. First, I found an old copy of a first-hand account of an orphanage in Naples, called The Casa Materna Story. Second, I read General Mark Clark’s autobiography, “Calculated Risk,” about the U.S. Fifth Army’s invasion and progress through Italy from the south. And finally, just last week — I found the book I didn’t know I’d been waiting for: Mussolini’s Daughter, by Caroline Moorehead. This book explains what never fully made sense to me.

How did Benito Mussolini rise to power? How does a country with a history of democracy hand itself over to a dictator? How did it happen? And could it ever happen again?

The answer is complicated because humans are complicated. The factions vying for influence within Italy during this time were a series of “ists,” — Socialists, Communists, Fascists, and Liberals. Add to this combustible soup the existence of the Vatican in Rome and a history of distrust among Northern and Southern Italians, rampant corruption, and mafia activity. All that chaos led to a certain hunger among the people for someone — anyone — to take charge.

In Italy, that leadership came in the form of a five-foot-seven, strong-jawed man, with a penchant for making speeches. Benito Mussolini, a former writer/journalist and Army veteran began gaining influence among his fellow fascists. He was elected to Parliament as a member of the National Fascist Party. Mussolini believed violence was a justified means to reach certain ends. Mobs set fires and wielded clubs, knives and guns, to break up union strikes and get people back to work. Fascist squadristi used their past military service to form a club of “warriors” with a shared experience of war. Mussolini believed that Italy had grown “soft,” the men too feminine, the women too masculine. He called people to take up arms.

And then, in the summer of 1922, he staged a march on Rome and demanded King Victor Emanuele III install him as Prime Minister. The King had enough military might to squash this uprising. But he was more concerned with maintaining his family power than he was about protecting the Italian people. So he made a deal with the Duce. He gave in, handing Mussolini exactly what he wanted: everything.

At first, Mussolini trumpeted the essential nature of the traditional family — a husband-provider, and a fertile wife at home with many children — even as he cheated openly and frequently on his wife and left the child-rearing to nannies. He took control of the railroads, the newspapers, and other essential services like schools. He envisioned a stronger, more virile nation, both an echo of the Roman Empire of the past, and a clarion call, inviting all Italians to participate in a new Italy of the future.

Well, not all Italians. He regularly made fun of cosmopolitan couples who lived in big cities with little dogs — dogs, he said, that were poor replacements for children. He quieted any and all opposition. (I've always thought: if you have to imprison your opposition, then your position must not be all that strong in the first place.) But alas, all this, in the name of leadership. All this, in the name of securing a brighter, more stable future for Italy.

And here’s the real kicker: for a while, it worked.

One thing I’ve learned, in all this research, is that when life feels painful and uncertain, people long for strong, decisive leadership. When we feel lost, we long for someone — anyone — to tell us what to do, what to believe, and how to live.

It’s seductive to be told that someone at the top knows exactly what they’re doing. We long for someone to show us the way.

On its head, this shouldn’t really be a problem. Leadership has always been a quality that I hope to instill in my children. When you’re on the playground, don’t be the one to wait to be included — be the includer. If you want to have more friends, practice the most powerful sentence known to man: “Hi, I’m _____, what’s your name?” Leadership can sometimes mean action. But more often, leadership that leads to flourishing is less about action and more about humility.

You have to care more about the people than you do about the power.

Mussolini only cared about his power. He grew paranoid and established secret police and vast networks of spies (and spies hired to spy on the spies) — creating massive files on private citizens, reading their mail, transcribing phone calls, and more. Then, in 1939, the first truly important decision came to his desk. The time had come to decide with whom to place his allegiance. Would he join forces with Great Britain and France, or choose to fight alongside Adolf Hitler’s Nazi Germany and the Japanese? In the end, Mussolini’s deep insecurity and greed for power made the decision. Adolf Hitler invaded Poland, and told Mussolini that he would move forward with or without Italian aid. But Mussolini could not stomach being seen as weak. He couldn’t fathom aligning with Great Britain, and missing out on the possible spoils of war. And so, he made the decision. Italy would fight with the Nazis.

Perhaps it’s just because I’m reading so much about Italy. But I seem to be seeing echoes of this history everywhere.

I see it in China’s President Xi, who uses state power to hold an entire nation hostage in the name of the so-called “Zero Covid” policy, which was never feasible or advisable in the first place, only to pull back on that policy, to maintain power, after an unprecedented popular protest.

I see it in Vladimir Putin, who censors news in order that only favorable reports are seen from the inside, despite the truth of his war crimes, laid bare to outside witnesses.

I see it in certain U.S. politicians, too. We’re witnessing political parties (on both sides) fracture into factions. This will inevitably lead to vacuums of leadership — and open opportunities to grab for power. We’re only a few months away from the beginning of a new election cycle. I’m certain: the timeless allure of the strong man (or woman) will rage on.

I don’t know what any of it holds for the American future. Or for the world.

But I do know this one thing. I learned it an AP class, my junior year of high school. History repeats itself, over and over and over again.

Keep your eyes open. Dictators aren’t born. They’re elected.

You received this email because at some point in the past, you expressed interest or signed up for email updates. I hope the words bring a bit of encouragement to keep entering into the (mostly) dark forest we call life.

Recent Favorites

BOOK:

The Relentless Elimination of Hurry by John Mark Comer. I gave this book as a Christmas gift to about half of my family. The commentary on the sheer madness of our current pace of life is hard to read, at first, but *hopefully* liberating, too. Commenting on the loss of a culturally enforced Sabbath, he writes: "It’s easy to just assume this pace of life is normal. It’s not. This ‘time famine’ we grew up in is relatively recent. My question is simple: What is all this distraction, addiction, and pace of life doing to our souls?”

WATCH:

Stutz (Netflix). Actor Jonah Hill interviews his therapist, Phil Stutz, in this documentary full of wisdom and heart. It left me and Patrick with so much to discuss. Phil Stutz says the three aspects of reality are “pain, uncertainty, and constant work.” If you watch it, I’d love to hear your thoughts!

One Last Thing:

Like everyone else, I’m re-evaluating the use of my time during the new year. I am trying to make a decision about whether to commit to writing this newsletter weekly or bi-weekly. Do you have an opinion? If so, reply to this newsletter to weigh in. I’d love to hear your thoughts!

—CG

I agree with Jane Anne. These are so wonderful, but we all know time is precious. If you did them less regularly, perhaps once a month rather than once a week, or even just when the spirit hits you, your readers will surely be contented. May 2023 bring you time in spades!

I always enjoy reading your insights, reviews and anecdotes. It would take me hours to write my thoughts so carefully and express them only half as clearly as you do in these entries. As a fellow time analyst, I'm engaging in making "the list" to sort and prioritize: What moves me forward, serves God and others and brings me peace while allowing time for spontaneity and the unexpected? I sense you did this in 2022, but if you need to do more in 2023, your readers will understand. We'll be here when you're ready to resume. 🙂